Longtime champion of local food, Glenda Bartosh, turned her attention to apples this week, and discovered that our very own Traced Elements regular, Mike Roger, is quite the apple man. Glenda gave us permission to repost her column here.

Apples, apples, apples. They’re everywhere this time of year, especially southern B.C., including Sea to Sky, so you don’t have to hit the Okanagan.

From West Van to Birken and beyond, you’ll find apple trees, babied and pampered, dwarfed and full-sized. And neglected old troopers that tug at your heartstrings—twisted and tortured, maybe 100 years old—still bearing fruit, in yards, orchards and ditches, where the goodness is yours for the taking, as gleaners well know. Even Whistler has a tree or three. (Ask Feet Banks about them apples.)

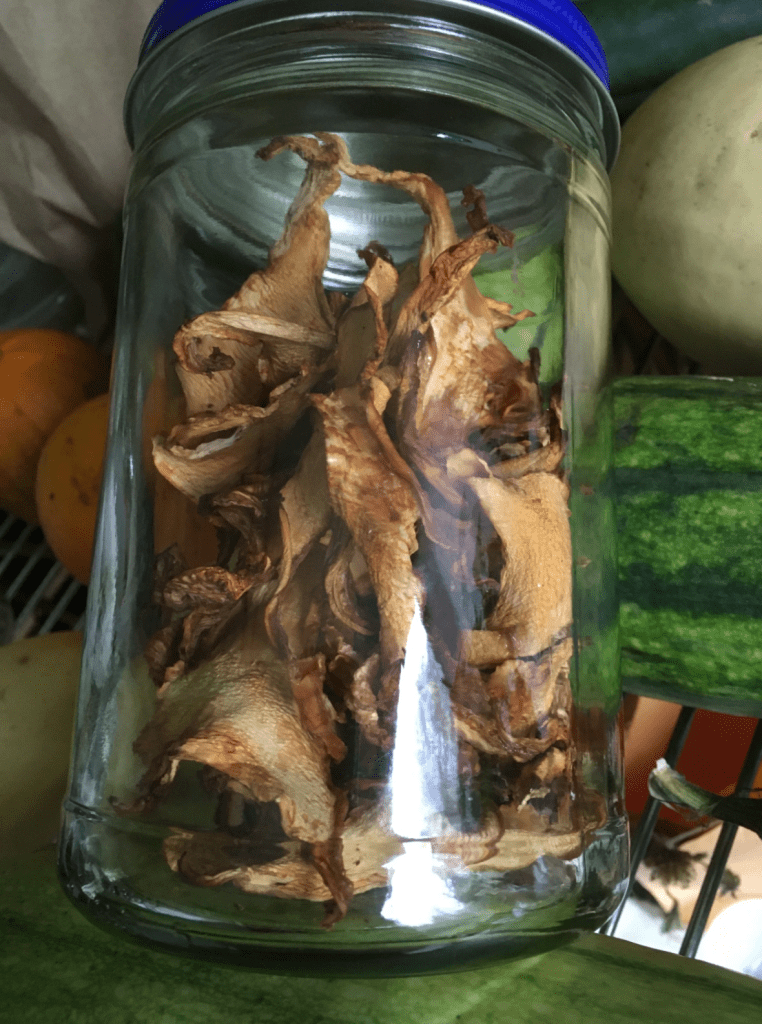

Fresh juicy apples; dried apples; apple chips. Apples baked, boiled, canned and pied. My 92-year-old mom, who’s lived a long and happy life eating many an apple, recommends a dab of peanut butter on an apple slice.

If you’re of a certain age or from the prairies, you’ll smile at the memory of bobbing for apples (the apples were bobbing, hopefully not you!), and the sing-song “Hallowe-e-en a-a-apples!” called out on doorsteps when, truth be told, we were hoping for candy, not apples at all. And who’d ever want one now in their trick-or-treat bag?

Poor apples! They’re so common we take them for granted, not realizing what a rich and noble lineage they come from, and how good they are—for health, nutrition and pleasure—especially those heritage varieties.

We have some 7,500-plus kinds of apples on the planet, but most of us can name, maybe, six. McIntosh—the original big Mac—so ubiquitous in Ontario, where it was first grown by one John McIntosh, in 1811. Delicious apples from the States. Spartans, created by R. C. Palmer in Summerland in the 1930s by crossing Macs and a pippin. Maybe Galas and Ambrosias, and the ever-green Granny Smith, a friendly apple from Australia, circa 1868.

But how about Grimes Golden, which could be a rockstar? Or the Hubbardson Nonsuch. Blacktwig. Buckingham (The Queen). Greening from Rhode Island, going back to 1650. The Gano. The Gennet Moyle. All poetic, and all apples grown in southwestern B.C. since the 1850s, and now sought after by many a heritage apple buff and association, including the Royal B.C. Museum, UBC’s Botanical Garden and Mike Roger of Willowcraft Farm near Birken.

Mike, who plants six apple trees a year, is known for helping out on older farms dating back to the 1950s and bringing heritage apples such as sweet Annanas; super-tart Cox Orange Pippins; or humungous Boskopps (great for cooking) to Sea to Sky farmers’ markets.

“The heritage varieties are usually grafted onto full-sized trees, like, 30 feet [9.1 metres] tall and 25 feet [7.6 m] in diameter, so they’re massive. They can give several hundreds of pounds of apples,” says Mike, who’s also known for making amazing apple juice—150 litres in a few hours—by running a gunny sack full of ground apples through a top-loading washing machine on “spin.” (The juice pours out the drain hose—how excellent is that?) Recent commercial varieties, by contrast, are grafted onto semi-dwarf or dwarf rootstock so they’re easier to pick.

As for that noble apple lineage, cast your mind back 10, maybe, 12 thousand years, to the earliest proto-apples in Neolithic Britain and Europe—wizened little things, more like crabapples.

Wild apples spread like crazy, but what we think of as an apple today most likely came from the Caucasus Mountains of Asia Minor, near where 17th-century historians located the Garden of Eden. BTW, there’s no scientific evidence confirming it was an apple that tempted Eve. It was just (forbidden) fruit, possibly a fig or apricot.

We have Ancient Romans to thank for breeding apples for size and taste, although they don’t grow true from seed (ergo the above-mentioned grafting). Plato, for one, could name about two-dozen apples, and in ancient Assyria, apples were served at a wee gathering for 69,000-plus people hosted by the king. A thousand oxen were also on the menu.

Apples are a key ingredient in classical Arabic cooking. I love how Farouk Mardam-Bey in Ziryab: Authentic Arab Cuisine points out that at the centre of every apple, we’ll find a five-pointed star, “the symbol of knowledge and power.”

As for an apple a day keeping the doctor away, it’s true. All the fibre in apples is good for your gut, plus it helps you feel full. Several studies show that apples’ polyphenols help prevent heart disease and lower the risk of stroke, while the flavonoids and anti-oxidants could help fight cancer.

University of Michigan researchers, who concluded that apples’ only health benefit was an avoidance of prescription drugs, analyzed just how big that beneficial apple should be: At least 7 centimetres in diameter and 149 grams. But an Italian study showed significant benefits in reducing heart disease and cholesterol when people ate two apples a day versus consuming the same amount of sugar and calories in apple drinks.

If all this makes you curious about branching out, ahem, and re-thinking apples, excellent. And if you’d like to branch out when the snow flies, and try some lovely homemade baking featuring all kinds of apples—maybe even from their own orchard in Naramata—head to Ian Gladstone and Joni Denroche’s cozy cafe at Cross-Country Connection in Lost Lake Passivhaus, just a short walk from Lot 5 in Whistler Village.

Joni’s taught me a great new trick: Simply wash, core, then slice your apples and freeze them. Use them, as is, for baking, or freeze them on a pan before bagging, so they don’t stick together. Voilà! A “super-cool” snack straight from the freezer.

Glenda Bartosh is an award-winning journalist who tips her hat to everyone who helped with these apple tales, including my mom, Feet, Mike, Joni, Ian, Bob Deeks, Lisa Richardson, Pauline Wiebe, Cate Webster, Paul Burrows, and Bob Brett. Long live the apple buffs!