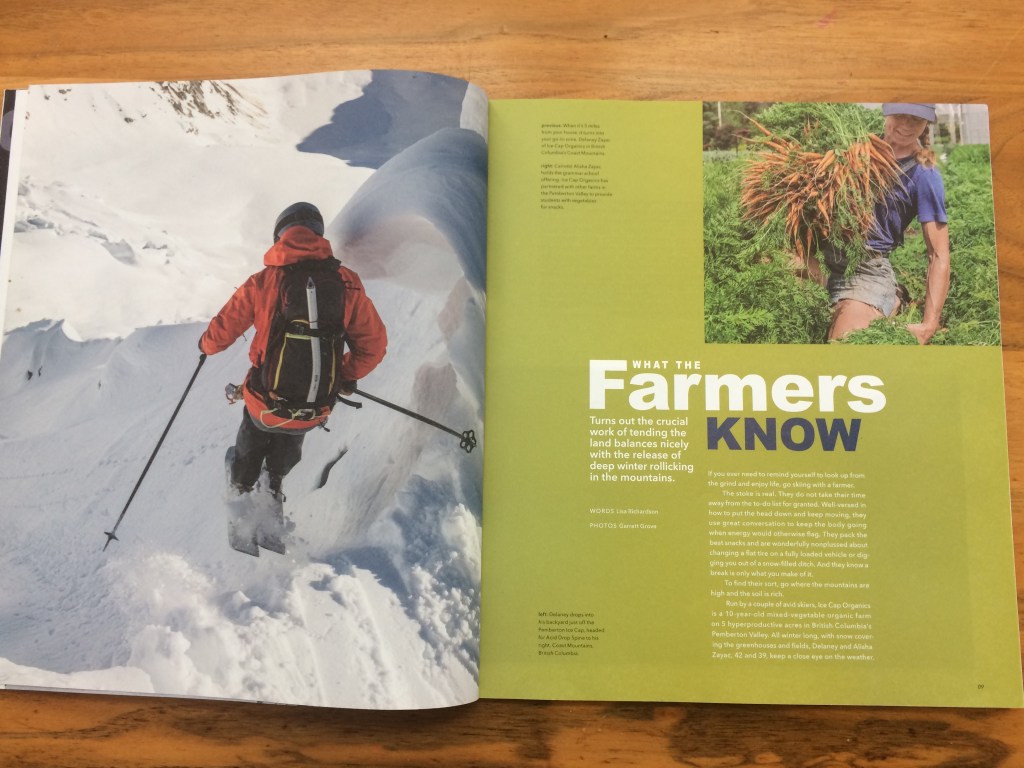

Turns out the crucial work of tending to the land balances nicely with the release of deep winter rollicking in the mountains.

If you ever need to remind yourself to look up from the grind and enjoy life, go skiing with a farmer.

The stoke is real. They do not take their time away from the to-do list for granted. Well-versed in how to put the head down and keep moving, they use great conversation to keep the body going when energy would otherwise flag. They pack the best snacks, and are wonderfully nonplussed about changing a flat tire on a fully-loaded vehicle or digging you out of a snow-filled ditch. And they know a break is only what you make of it.

To find their sort, go where the mountains are high and soil is rich.

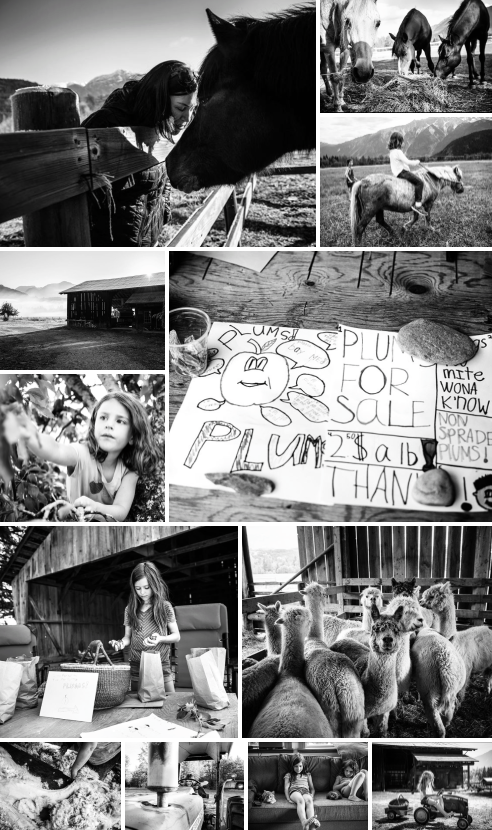

Run by a couple of avid skiers, Ice Cap Organics is a ten-year-old mixed vegetable organic farm, on five hyper-productive acres in British Columbia’s Pemberton Valley. All winter long, with snow covering the greenhouses and fields, Delaney and Alisha Zayac, 42 and 39, keep a close eye on the weather. And whenever the conditions are right, Delaney, is up at 3 a.m., blazing out the door, skinning in the dark with headlamps to pursue objectives out on Miller Ridge or Duffey Lake Road with a small crew of friends. Alisha often opts to show their kids what’s to love about winter.

The volcanic-rich river-silt blessed soil of the Pemberton Valley has earned many farmers’ attention, but it’s the massive Coast Mountains that catch the farming-skiing type. And if the mountains bring folks in, it’s sometimes the farming that gets them to stay—loamy earth beneath 8,000-foot mountains, and living to the sound of glacier-fed rivers.

“It’s why we’re here,” says Alisha. “Winters off is one of the things that drew us to farming,” explains the former tree-planter and agro-ecology scientist. “We love farming, we believe in it, and this is what we want to do, but we chose Pemberton, because we wanted mountains. We canvassed the world, to find places where you have mountains and farmland – Bella Coola, Pemberton, Chile, a couple of places in France.”

Delaney reflects on their decision-making process—a couple of young nomads who were dividing their year into three seasons—university, tree-planting, travelling or skiing. He’d spent his twenties and early thirties skiing over 100 days a year, bumming throughout the Canadian Rockies, Kootenays and Coast Range, and venturing farther afield to the Andes and the Alps. It was time to root down and think about having a family but Delaney knew that without big mountains there was no chance of his calling a place home. Pemberton was fertile, steep, proximate to a hungry market, and permanently set to stun—a place where there are no ugly views.

Now their year breaks into two parts: farming season, and winter. As the farm sleeps, the pair take turns driving their vegetables down to winter markets in Vancouver, a city of 2.5 million people two hours to the south. They make plans, research the latest science and developments in farming, ski, and regenerate. “We work hard in the summer, and play hard in the winter.” Every morning since completing the 10-day silent Vipassana retreat she’s wanted to do for decades, Alisha wakes up before dawn, before the kids, 6 and 8, have roused, to sit and meditate for an hour, watch her mind, and bank some equanimity for the day ahead. Delaney plans his last spring mission to the remote Waddington Range. Bad weather days, they tackle the farm chores, like sourcing an old upright freezer from a Chinese grocery store that they can upcycle into a germinator for their seed starts.

Then, come growing season, they take up their mantle as activists.

“That’s another reason we started farming,” says Alisha. “It was a way to align with our values, a positive way to be part of the community. I wanted to fight the good fight for agriculture and as soon as I started farming, I realized this is actually enough.” It’s a quiet, radical activism.

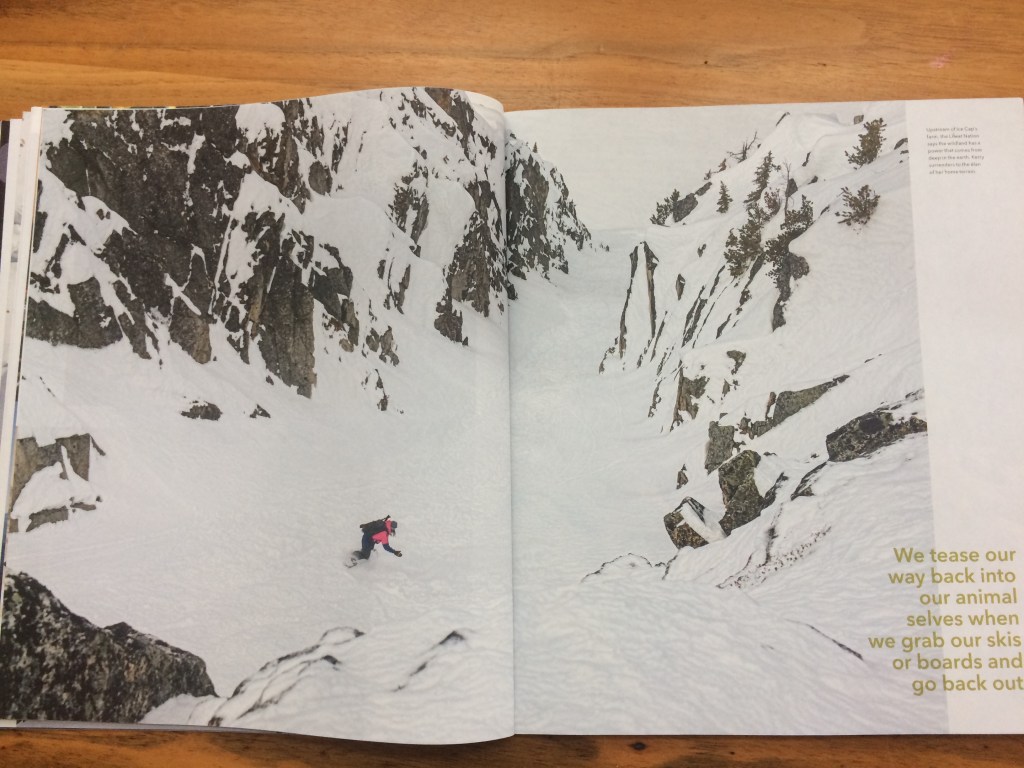

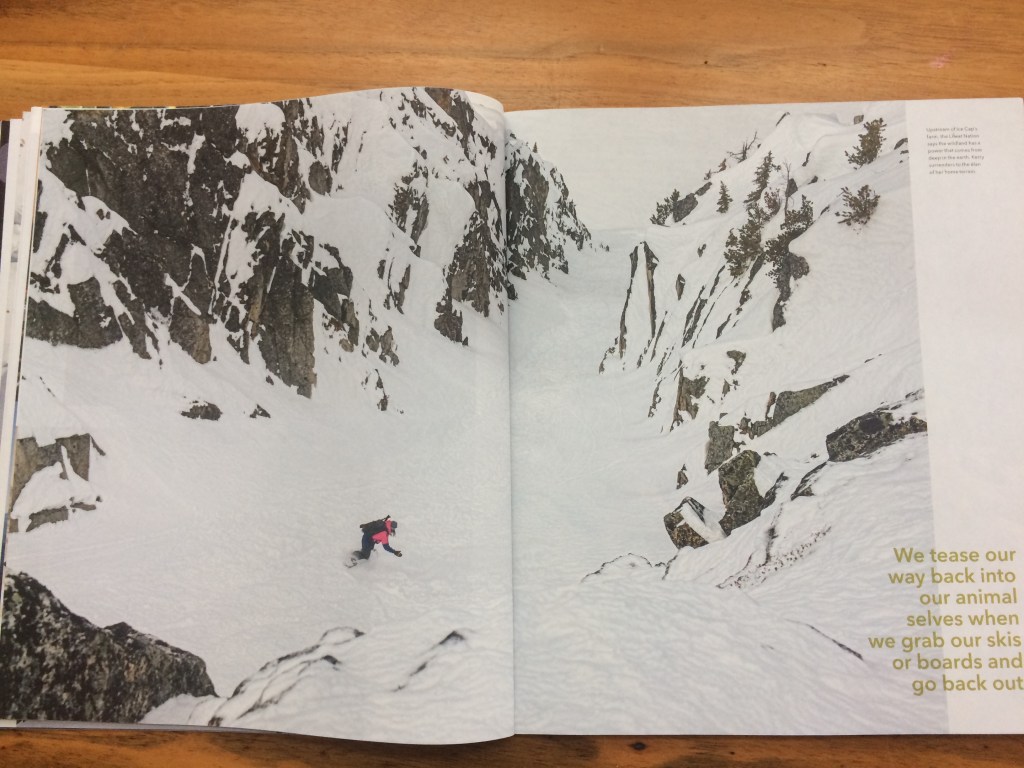

After he’s been at the markets in the city for the weekend, the first thing Delaney does is park the truck, grab the kids and walk around in the fields together, see how things are looking, noting the growth and changes that have unfurled in the last three days. The Lillooet River runs past the end of the narrow, pot-holed street, flowing down out of the ice-cap and past the sulfurous thermal sleeping volcano that still vents steam out its fumeroles. The Lil’wat Nation, whose traditional territory this is, says the wild land upstream of Ice Cap’s farm has a power that comes from deep in the earth. It’s so big and powerful that when he skis back there, it gives him goosebumps. He treads the soil of the farm to shake off the city, touch down, ground down, and tap quickly back into that energy.

Winter gives it the time to seep in.

“Every farm has its own personality,” says Amy Norgaard, who’s worked at many farms in the Pemberton Valley, including Ice Cap Organics.

Amy, 26, grew up in western Canada, in the 7,000-person ranching and logging town of Merritt, British Columbia, skiing and snowboarding obsessively from the age of two. When her mom got breast cancer, Amy, then in high-school, discovered that vegetables are potent and delicious medicine. Later, she floundered through university courses until discovering the faculty of Land and Food systems—that’s when Amy found her people.

“I took my first soil science course in 2013 and it literally changed my life. I started learning about farming systems and their complexity and beauty and the complete mess we’ve made with food production.” Two years later, to acquire her final six credits and prove to herself that her romantic idea of farming probably wouldn’t withstand reality, she interned as a farmhand for eight months at Ice Cap. All the pieces fell into place – her love of the mountains and her understanding that being stressed is completely different from working hard. She farmed so hard that years of brain-spinning insomnia disappeared, allowing her to fall asleep exhausted and satisfied.

Of course, the skiing helped.

For the last eight years that he has lived in Pemberton, Andrew Budgell rented a poorly insulated cabin near his farm fields, tucked off the narrow road in a giant grove of cedars. Winter is the only time he’s not covered in dirt, but the price he pays is in “cold.” Some days, it was so freezing, he’d blast hot air in his face with a hair dryer to bring himself back to life.

“He calls it the comfort gun,” says his soft-spoken farming partner, Kerry McCann.

Andrew, 44, and Kerry, 36, met in Pemberton eight years ago, when Andrew, a ski-bumming boot-fitter in Whistler and refugee from the suburbs of Ottawa, decided to experiment with growing salad greens as a side hustle. He knew nothing about farming, except that he wasn’t afraid of hard work, loved learning, and wanted to attune more deeply to the rhythms of the earth.

McCann, a beekeeper, yoga teacher and cranio-sacral therapist, had been working as the “hands” of an arthritic physiotherapist in the economically depressed community in Ontario where she’d grown up, home-schooled, on a self-sufficient homestead run by her back-to-the-lander parents. Changes in the health insurance legislation meant her work was drying up, so she ventured west, and stopped in the first place she found that had seven pages of help wanted ads in the newspaper – the Whistler-Pemberton corridor. She convinced her landlord to let her install garden beds alongside the field where Andrew was growing his greens. As her seasonal job as a park host wound down, Kerry began to ponder her next move when Andrew proposed next-leveling his salad bar. “Maybe we should start a farm? I can’t do this alone. We’ll get bees!”

Kerry is an instinctive grower. Where Andrew acquires knowledge through his brain, poring over books and websites, and studying dewpoint and freezing level and weather models, Kerry’s insight into the natural world flows through her actual pores – she will walk outside, sniff the air and announce, “Frost is on its way. We should cover the vegetables.” These approaches define their skiing styles, too: Andrew studies maps and trip reports; Kerry rests on instinct.

Seven years into operating Laughing Crow Organics – their certified organic mixed vegetable farm – they’ve doubled income and veggie production almost every year. But Andrew says, “The reality is, we’re both very challenged in pulling this off. We are living and breathing this farm dawn until dusk.” Farming, just like hiking and skiing your ass around the mountains in temps that turn any exposed hair into icecicles, is not an easy endeavour.

But they always eat well, and when winter arrives, they forget their 30-item daily to-do list and head for the hills.

Kerry spent years meditating and practicing yoga; skiing is her winter practice, exploring the backroads and drainages and skin laps around Pemberton. “I used to spend a lot of time looking for enlightenment. But when you’re skiing powder, it’s a kind of samadhi,” she says, referring to the yogic word for oneness, or meditative absorption, the goal of all her sitting. It’s a kind of short-cut.

Increasingly, Amy is part of Laughing Crow Organic’s winter crew too. After several seasons with Ice Cap, she went to graduate school to study soil science. She skis every chance she gets. “Part of the connection you gain from farming comes from being so exposed to the elements. There’s a lot of vulnerability. You don’t know what the day is going to look like, and you’re vulnerable to what Mother Nature wants to do to you.” She thinks about this when she’s out skiing, too—the natural synergy between mountain people and growers, and how they understand the thrill and sense of vitality that come from being immersed in the elements. The honest exhaustion at the end of the day’s effort. The risk, the reward of getting out among it.

Most of the modern developed world is a set of systems and habits and structures designed to limit our exposure to nature and keep us safe from variability, from discomfort or physical labor, and help us not even break a sweat. We tease our way back into our animal selves when we grab our skis and go back out. But the illusion of separation remains, constantly reinforced every time we jump into a vehicle, order a coffee to-go, stock up at the grocery store where an invisible, complex, global supply chain presents us with the illusion of a constant steady supply of fuel, of food, insulating us from our true vulnerability on this delicate earth.

It’s good to sit with that: what the skiing-farmers know.

This story was featured in Patagonia’s Winter 2020 Journal. All images captured by Garrett Grove.

Follow IceCap Organics on instagram at www.instagram.com/icecaporganics/

and Laughing Crow Organics at www.instagram.com/laughingcroworganics/