“EVERY FARM HAS ITS OWN PERSONALITY,” says Amy Norgaard, a soil science student at the University of British Columbia, and former farmhand and market manager with Ice Cap Organics.

Her two-year-long Master’s thesis, which she will defend in late spring, required her to travel between 18 different organic farms across southwest B.C., the Pemberton Valley, the Fraser Valley and Vancouver Island’s Comox Valley, to collate data about nutrients and soil amendments.

At first, she thought this was going to give her the golden key to running the Ur-Farm, the perfect organic system, as she compiled tips and best practices from all the farms she was visiting and researching.

But what she discovered is, there is no homogeny in small-scale, mixed-vegetable organic farming. And the idiosyncracies, in contrast to Big Ag’s monotony, work. “I’m working with this very niche group and yet none of these farms look the same!” she exclaims.

Norgaard is an endearing combination of exuberance and intensity when she’s talking about her passions, of which snowboarding, soil and the tastiness of Pemberton-grown vegetables rank high. Now 27, she grew up in Merritt, hunting with her dad, and ripping around the mountain at Apex. She loved animals, worked at the local vet clinic, kept chickens as part of her 4H club program and captained every sports team she played on. She studied kinesiology for a while and hated it, took a season off to live in Whistler and snowboard every day and spent summers firefighting. Then, she stumbled into a soil science course. It was life-changing.

She started learning about farming systems and their complexity and beauty and “the complete mess we’ve made with food production.” Two years later, she interned for eight months at Pemberton’s Ice Cap Organics to get her final six credits and dissolve what seemed to her to be a romantic idea about farming. It didn’t work: She loved it.

Norgaard is still enchanted by the mystery of soil, and how, as much as we might have learned in the last 50 years, we’re realizing how little we understand of the infinite complexity of this system. “Soil is the basis of life,” she says. “This thin layer of topsoil we have on Earth is the medium for everything we depend on. Literally. For food and forests, for carbon cycles, for everything else it does like filter and hold water, and cycle nutrients. Literally, without soil we wouldn’t have a medium for decomposition.” And it’s one-metre thin—akin to a single cellular layer of skin on our bodies. And like our skin, it’s holding everything together. “Civilizations rise and fall with their soil management. It’s considered a finite resource in relation to our human lifespan.”

The goal is not to measure soil quality, but orient towards soil health. Health is an important reframe, because soil is living. “It’s super offensive to a soil scientist to call it dirt, because dirt is inert. There’s no life in dirt. But soil is life.”

And as much as a farm is a product of its landscape and its soil health, it’s also a reflection of the personality of its farmers, and the values and intentions they pour into it, liquidized as sweat.

‘FARMING WAS A WAY TO ALIGN WITH OUR VALUES’

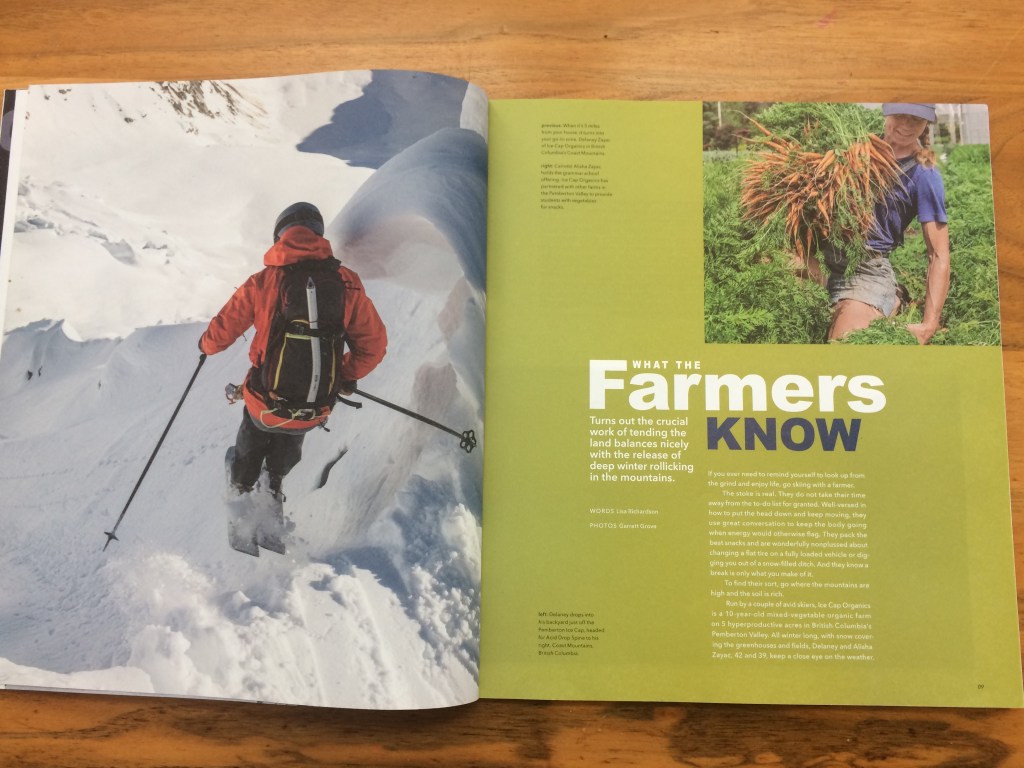

When I first met Delaney and Alisha Zayac, they had one season under their belt running Ice Cap Organics, their mixed-vegetable organic farm. They’d just bought an old house on two hectares in the Pemberton Valley between the Lillooet and Miller Rivers, and had a baby. Having tree-planted and run tree-planting crews for the last decade, they knew how to work hard. They’d read Vandana Shiva, the legendary food security activist, and Shiva’s writing prompted Alisha to transfer out of marine biology and into agroecology. An internship with Helmers Organic Farmhad put Pemberton on her radar. But at the beginning, it all seemed like a high-stakes gamble. Their five-year goal was ambitious, and yet not: they wanted to still be farming, and to work out how to have one day off a week.

Fast forward to 2020. Would they tell their younger selves to change course, and try an easier life?

“Definitely not!” says Delaney.

“No!” echoes Alisha. “The other way around. It’s amazing.”

It took some time to find the balance, between pouring everything into getting the farm going, and making time for themselves, for family. Ten years in, it’s manageable. But it’s still exciting, because the only constant is not-knowing. “You’re constantly making decisions,” says Delaney. “What amendments you’re using, what you plant where, how you’ll harvest different things, what tillage equipment you’re going to use. You’re doing it so constantly, and every decision has such weight in terms of outcomes, that you really feel you are part of the process. You’re connected to the ground. If I go out there and it’s time to start planting, and I till up a bunch of land too early and make it all crumbly and into little balls of mud, by making that one wrong decision I’m going to totally affect the fertility of that soil, and I’ve done that and seen what happens.” The farm becomes a literal manifestation of their intentions, decisions, and actions, for better and worse.

One year, late in May, Delaney hiked up the ridge above Ice Cap Organics and looked down. He saw it suddenly, not as a manifestation of hundreds of decisions and learnings and missteps and logistics, but as a creative work, a personal expression of the two of them.

It’s their version of marching for the climate.

“Being an organic small-scale farmer, in some ways, is being a radical activist,” reflects Delaney. “It actually has more of a tangible impact on community and on ecosystem than protesting at the anti-world trade. I support that, too. I want to see change. I want to see big change in the world. We both do.”

When they were in university, they realized that more than running around and talking about change, they wanted to be the change. They wanted to put their life’s work into something that manifested positive progress.

“Farming was a way to align with our values,” says Alisha. “As soon as I started farming, I realized, this is actually enough.”

But it’s not just a one-day march, after which you get to leave your signs in the gutter and go home. Small-scale organic farming is an all-in business—a complex one to operate at the level of intimacy that two hectares and a family operation demand. “Farming isn’t just a manufacturing business where you get 1,000 parts made in China and ship them over and sell them,” says Delaney. “You are actually producing. You’re managing the production on the farm, you’re managing sales, you’re managing all the systems—the irrigation system, soil-health system, greenhouse system, staff.”

Ice Cap Organics plant, weed and harvest mostly everything by hand, pay fair wages and use farming practices that make the ecosystem healthier and more diverse. On their website, they explain the value their community-supported-agriculture (CSA) subscribers get when they sign up for a season (20 weeks) of harvest boxes. “It is cheaper to grow a head of lettuce on a 500-acre mono-crop lettuce farm in California with poorly paid migrant workers, massive capital infrastructure and harvesting equipment.” But, because buying direct from the farmer eliminates the middlemen in the supply chain, a consumer pays about the same.

So the question is not just what are you having for dinner, tonight, but what system do you want to invest in? What world do you want to help manifest?

Charles Massy, author of Call of the Reed Warbler, and a leading voice for regenerative organic agriculture—the use of farming to tend the soil and nurture living systems, rather than exploit, poison and deplete them as industrial monocropping tends to do—says regenerative agriculture is nearly two-and-a-half times better at burying carbon in the ground than anything else. “I see it as one of the very best solutions for global warming,” said Massy in a recent visit to Patagonia’s Ventura headquarters. “Since the Second World War, we humans have destabilized nearly all of the natural systems. We’re destabilizing things to the point where our own survival will become an issue. Yet because everything is integrated in a healthy system, with regenerative agriculture, there are all these positive knock-on effects—we store more water, we stop erosion, we encourage biodiversity. And it’s not just farmers that can get into this. The regenerative agriculture movement will only work when their products are supported by the urban community. It’s a two-way partnership and together we can really start addressing some of these major challenges tipping us towards [extinction].”

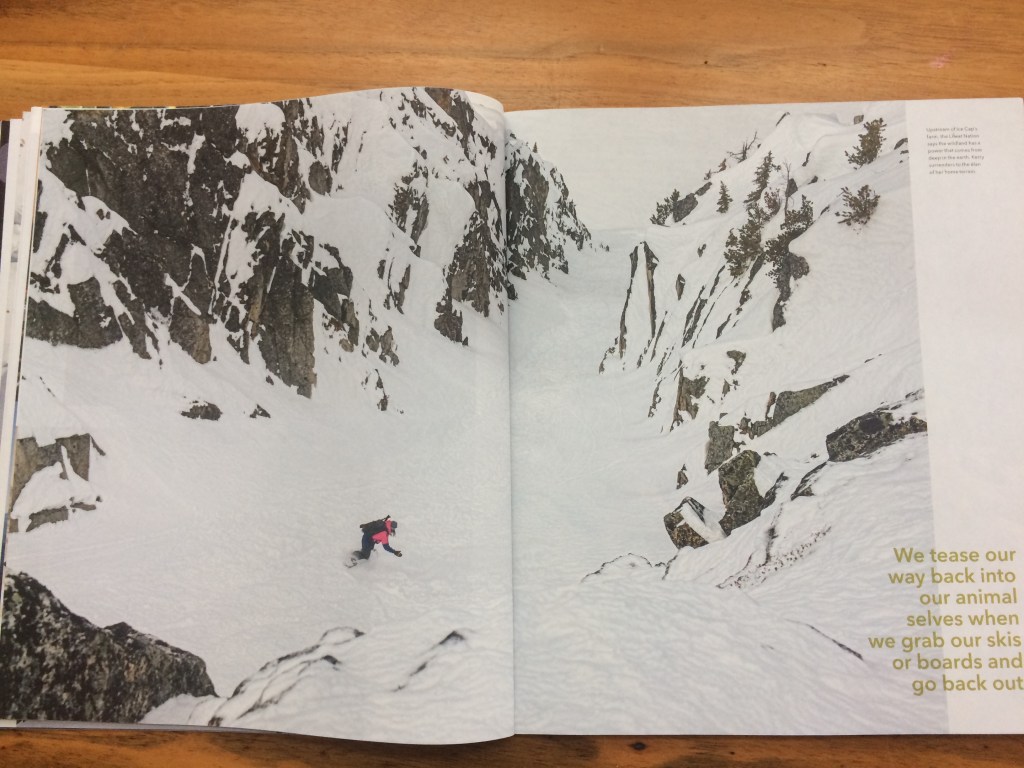

The Zayacs can attest to how much more embedded in the climate and landscape they feel since starting their farm. “There’s something about just staying in one place and working the same land, for year upon year upon year,” reflects Delaney. “A big part of our being is invested in this ground here.”

They’re also embedded in the community in a way they weren’t before.

Explains Alisha: “Before the farm, we were part of lots of little bubbles, but here, you’re farming, harvesting your vegetables, putting your vegetables in the truck, taking them to people in Vancouver.” It’s an intimate, hand-to-hand transaction. She can easily imagine their customers cooking up dinner for friends later that night. Delaney says that, with a couple hundred people visiting them at market, he can mostly remember each face. It feels like mycelium, the exquisite interconnected branches of fungi that make soil healthy, through which plants communicate and share nutrients—a living network.

It’s deeply meaningful. And yet, it’s constantly humbling. “Little things happen all the time to let you know you don’t have it all figured out,” says Delaney. “Farming is a lifelong learning process. And at the end of the day, we’re just growing some veggies.”

‘OUR SUCCESS IS ALSO EVERYONE ELSE’S SUCCESS’

Rootdown Organics started the same year as Ice Cap—and both benefitted from mentorship and enthusiasm of the Helmers. The organic ecosystem of the Pemberton Valley has since expanded to include community-supported-agriculture (or harvest box) offerings from Laughing Crow, Plenty Wild, Blue House Organics, and Four Beat Farm. The Pemberton Farmers Market has been named the Farmers Market of the Year in the medium (21-to-60 vendor) category, organic flower farms are sprouting up, North Arm Farm is still a stalwart, and using the metric of residents per brewery, Pemberton was just voted the Best Beer Town in B.C. by The Growler, thanks to the Pemberton Brewing Company and the Miller family’s farm-to-tap offering, The Beer Farmers.

As small, mixed-vegetable organic farms have sprung up in Pemberton, the growers have had to work out how to micro-target within the regional market—selling to restaurants versus Vancouver markets versus Squamish and Whistler markets—so they’re not competing directly with each other. “This farming gig is hard enough,” says Kerry McCann and Andrew Budgell, farming partners at Laughing Crow Organics,“without stepping on one another’s toes. We are in competition, even though all our businesses are slightly different. But our success is also everyone else’s success. If the other farms in the valley can’t thrive and be successful as humans and enterprises, that reflects on our ability to achieve success, too. Everyone is pretty good at finding their specialty and overlapping as little as possible.”

Laughing Crow started eight years ago in a leased front field on Meadows Road on “a tight budget and a lot of hope.” They expanded each season, thanks to a Trojan work ethic and landowners Scott Lattimer and Lynne Menzel, who were willing to support their vision. It was exhausting, but the vision was strong: create a livelihood that would give back to the community, allow them to work for themselves, and not create a burden for the future generation to inherit. Last April, they moved their operation to 2.4 leased hectares at the Millers’ farm, which meant relocating and re-installing all their infrastructure—greenhouses, irrigation, washing and packing stations—from scratch, just as planting season was underway. On the plus side, it meant being able to tap into decades of farming know-how and the Millers’ intimate familiarity with the subtleties of the ground that Kerry and Andrew were now working. Not to mention, Bruce and Brenda Miller pioneered some of the first CSA mixed vegetable harvest box offerings in Pemberton almost 15 years ago.

With the Millers’ newest farm experiment, the wildly successful Beer Farmers, having turned their new address into a destination, it made sense for Laughing Crow to try their hand at agritourism, so last season, they set up an honour stand, planted out a huge maze of sunflowers and grew what would become known as “The Grand Majestic Pumpkin Patch of Pemberton.” Of course, it was all an experiment.

“We had a moment in July,” reflects McCann, “when we thought the sunflowers were going to bloom too early.” In their nightmares, the stunted maze would have suited only toddlers, but as it turned out, the sunflowers exploded into the most Instagrammed, beloved and feted event of the summer. “It turned out to be far more amazing than we anticipated. Neither of us had ever been in a field of flowers that big. The spectacle was really wonderful to be around and walk through. On top of the general beauty, the reaction from the community was really awesome. Everyone was so happy. It was infectious.”

It felt like a win, to not only feed people through farming, but also be able to entertain and educate. “We know firsthand how thought-provoking it is to wander through the fields, to appreciate the plants and wonder about the food, the soil and the bugs,” says Budgell. Often their day will start or end with a walk around the fields, taking notes to create the next day’s to-do list.

Inviting people onto the land itself—school groups, families, pumpkin hunters and sunflower lovers—was a way that Laughing Crow thought they could grow not just food, but activists and allies of the Earth and soil, as well.

“We’d like to think that a visit to our farm and a wander through a field of sunflowers loaded with bees will crank up the urgency knob the next time someone is faced with the hard data on how we are endangering these very things,” says Budgell, “maybe in different a way than reading something on the internet or attending a climate march in Vancouver. Humans are always far more likely to protect what they feel connected to. Plus, what better way to build community than to meet up at a local farm brewery, on a local farm, chat with your local buddies and farmers and go home with some local food from the farm stand?”

FEEDING THE SOIL, FEEDING THE WORLD

Project Drawdown makes the case for taking up your knife and fork for the climate. “The world cannot be fed unless the soil is fed.” At least half of the carbon in the Earth’s soil has been released into the atmosphere over the past centuries. Putting it back, through regenerative agriculture, is one of the greatest opportunities to address human health, climate health and the financial well-being of farmers.

One thing Amy Norgaard can say with certainty, having dug deep into soil health for the past two years, is that the Pemberton Valley hit paydirt when it came to soil. “You’re sitting on an amazing expanse of soils, which is a really valuable resource, not only for food production but for the ecosystem services that farmlands provide to society.” Don’t squander it, she urges. “It’s important for those soils to be managed well. That is often more expensive for the farmer, so as consumers, we need to be willing to pay for that land stewardship. We have to allow for the food to cost more. If farming isn’t a viable occupation, then those lands won’t be used for farming. Those beautiful meadows will become billionaires’ playgrounds and vacation homes.”

When regenerative farming is economically viable, Norgaard concludes, farmers do the hard work of protecting and stewarding the resource. It’s probably the yummiest way of contributing to positive climate action.

Earth activism needs fighters, warriors, protestors, policy makers, lobbyists, dreamers, repairers, regenerators. It needs us all. And as much, if not more, than anything else, it needs people to stand for the planet who know the smell of dirt under their nails, of sun on their skin and sweat on their brow, who know the joy of planting a seed and tending it, and harvesting it when it transforms into fecund and vibrant life. It needs us to sustain and nourish ourselves and each other, and to gather around tables of fresh healthy food, just plucked from the bed, still trailing the heat of the sun. It needs us to be attuned to the rhythms and cycles of the seasons. It needs us to know, with a deep cellular knowing, that even when you can’t see it, the life force is thrumming within, just waiting for the conditions to be right, just waiting for the right ally to come along.

And that is how you can eat your planet whole again. The formula is simple: Soil is life. Support those who keep it healthy. And by way of return on your investment, they’ll keep you healthy too.